EXCELLENCE IS A LOT messier than you think.

Thirty or so years ago, mental-performance coaches would spend hours and hours with Olympians, aiming to help them have a flawless event. “There was a lot of focus on being in the zone—in your flow state—and basically trying to set up the perfect performance,” says Sean McCann, Ph.D., who has coached athletes for 33 years as a senior sport psychologist for the U. S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee.

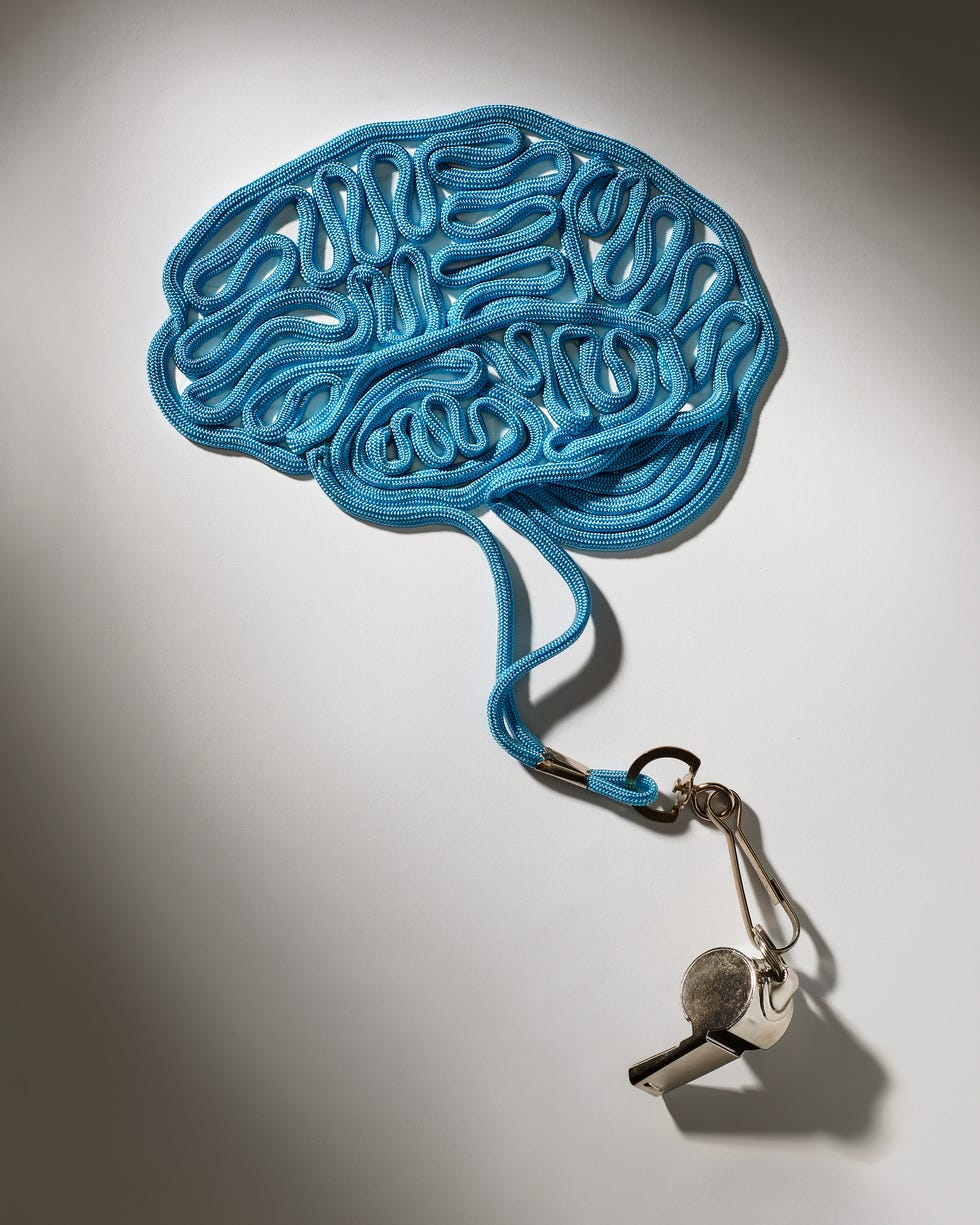

But perfection is rare; chaos is everywhere. (See: the 2020/2021 Games and, well, life.) As the ideas of mindfulness and resilience gained status in research circles and the zeitgeist as ways to manage that chaos, they took root and got results in high-performance training, too. Mental performance experts like McCann have started “focusing on moments of disruptive pressure,” he says. Those are the moments when standard mental skills like visualization aren’t working, because the situation overwhelms the resources that you have. It’s a high-stakes game or, on a more mundane level, a hot-button negotiation. You can’t go on autopilot; you need to be engaged, aware, and in control of your focus. “We’ve evolved into helping athletes figure out where their head is and be able to handle a lot of chaos, rather than seeking an elusive flow state,” McCann says. Handling chaos is about being skillful in navigating difficult moments. Olympians train their minds to be ready, resilient, nimble, and energized. But you don’t have to be a world-class athlete to benefit from high-performance thinking. We asked Olympic mental-performance coaches to share their new rules for winning at life.

Calmness Is Overrated

HELL YES, THERE’S going to be anxiety anytime the stakes are high. That feeling won’t go away if you judge and fight it, so start saying yes to it. “Understanding that most big performance moments are somewhat internally chaotic is really useful,” says McCann.

This normalizes the anxiety and removes its threat. Then redefine the energy. When athletes with pre-performance anxiety reframed their feelings as “excitement,” they performed better, according to a study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Similarly, you can switch your internal language from “pressure-filled” to “intense” and “electric,” says Michael Gervais, Ph.D., of Finding Mastery, a performance psychologist for major sports teams, executives, and Paris-bound Olympians. Taking the judgment and pressure away “helps you bring yourself forward to meet the challenge at hand,” he adds.

Everything Is Data

FOR MOST TOP athletes, performances that don’t hit the mark aren’t just things to shake off—they’re valuable data that helps inform and shape what they do next. “Olympians flex optimism,” says Gervais. “They tend to interpret events in a way that gives them agency and the opportunity to grow.” The more granular you can go on that data, the better the info you have to help you improve.

McCann says to consider what didn’t work: “Did you not like the outcome or not like the execution?” If you executed everything according to plan but your outcome fell short of expectations, then you probably didn’t have control over what happened anyway. (Someone else was faster that day.)

If, however, you weren’t happy with your execution, then “you have a million data points that are useful for the next performance,” McCann says. Pinpoint the triggers that moved you off course. Did you abandon your plan? Get distracted by something else? “Was it something you didn’t do, you can’t do, or just something you haven’t done before?” he says. Then ask, What’s the next opportunity to do something different?

Sometimes Things Suck

THAT OLD IDEA of taking a hit and pretending it didn’t affect you? Not so helpful. “One of the things that greats do more than they did 25 years ago is be honest with themselves,” says Gervais. “That’s one of the fundamentals for performance, because now you’re working from what’s true, as opposed to just interpreting things in ways that tamp down anxiety.”

Gervais knows it’s not always easy: He was consulting for the Seattle Seahawks in 2014 when they crushed Denver in one of the most lopsided Super Bowls in history, and also the next year when…they lost to the Patriots following a late interception thrown at the one-yard line. Brutal. “It would be a mistake not to feel all of that,” he says. “If you’re muted or you fear the depth of what those emotions might be, the unlock to performance isn’t available.

You have to feel it first in order to grow and learn from it.” Being honest with how much something sucks and your part in it—Gervais is a fan of journaling—helps build resilience for the next time you hit turbulence or worse.

Not Training Is Training

ROBERT ANDREWS, L.M.F.T, founder and director of the Institute of Sports Performance, has been a mental-training consultant to Olympic greats including Simone Biles and Simone Manuel. Andrews argues that, yes, hard work matters—but sometimes a grinding work ethic can steer you away from being a champion. Continuously thinking that you have to do more, more, more to get better results leads to hopelessness, not performance breakthroughs.

When Andrews coaches athletes and execs who work themselves to exhaustion yet aren’t getting results, he asks them, “What do you do to fill up your tank?” The answer should be more than taking a nap. “You have to find meaningful activity away from your practice or profession that recharges your batteries,” he says. Andrews tells stories of champions he’s coached who say that tank-filling changed their whole careers. There’s the athlete who walks to the beach many nights after dinner to watch the sunset. The one who gets together with teammates for Taco Tuesday. Another who goes around with a camera snapping photos here and there.

So important is stepping away and doing something refreshing that researchers called mental recovery time “the forgotten session” in a paper published in the Journal of Applied Sport Psychology.

It doesn’t have to be done solo. Research from Texas Christian University asked athletes which recovery strategies they used for mental performance. Those who listed “socializing” did better in their sport than those who didn’t.

It’s Not About The Result

SUCCESS IS THE result of setting yourself up for a strong finish; it’s not about focusing on the finish itself. Imagine you’re a 1,500-meter runner and you have a time goal. If you’re worried about not having enough gas for the last 300 meters on race day, you may hold back in the beginning. But if you have a plan—not letting yourself get behind too early, deciding where you’re going to be for the last 600 meters—“you’re focusing on the positive action,” says McCann. “Identifying what a really great race looks like and making a plan for it gives you a chance to have that great race.”

He stresses that having a series of steps that you can execute no matter what’s going on—your warmup felt weird, you had a testy interaction with someone on your team—is what makes success more possible. It’s less “What if I don’t hit my number?” and more “How am I going to go about getting that number?” You can’t control whether the merger talks will turn ugly or whether someone will have just a millimeter more kick at the finish line. What you can do is commit to a plan that puts you in the position you want to be in. That’s what leads to a win.