This is according to research conducted by ING, which also looks at how methane-reducing feed additives and other sustainability measures could influence production costs and competitiveness; how major dairy firms are addressing their scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions targets, and which how much carbon is emitted by some of the global dairy-producing regions.

According to the report, almost every company among the 30 largest dairy processors in Europe, North America, New Zealand, Australia and China has communicated a scope 1 and 2 carbon reduction target, while two thirds have set a scope 3 target.

ING estimates that the majority of emissions in dairy (80-85% upstream plus 10-15% downstream) are scope 3; these are indirect emissions that occur both up and down the value chain. The rest (around 5%) are scope 1 & 2 emissions, typically occurring during the production and transportation of dairy products.

The scope 3 targets set by major dairy firms are often intensity-based rather than absolute targets, which could ‘create tension with national emissions targets for agriculture that require an absolute reduction’, notes Thijs Geijer, senior sector economist and author of the report. The bank’s economist says that absolute targets are ‘gaining traction’, however, since these are often required by the SBTi, the non-profit that runs the only global framework for corporate net-zero targets in line with climate science.

Popular sustainability measures likely to drive up milk prices

Measures that are getting ‘a lot of attention’ in the industry – from methane-supressing feed additives to carbon sequestration and the introduction of anaerobic digesters – come with a range of challenges and would likely lead to milk price increases, according to the report.

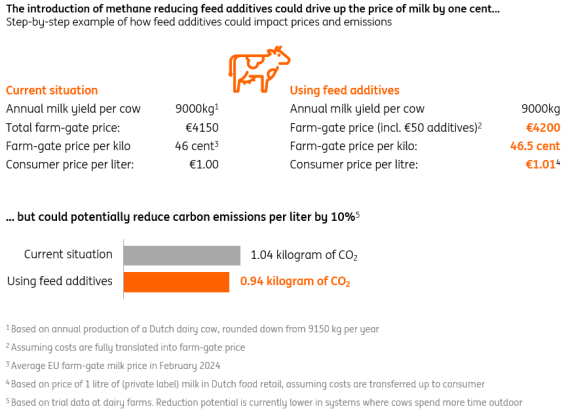

For example, ING estimates that the implementation o methane-reducing feed additives could drive up the consumer price of milk per liter by one eurocent – but also help reduce emissions by 10% per liter.

Meanwhile, building anaerobic digesters typically requires a steep one-off investment and produces expensive biomethane; while soil sequestration comes with a range of caveats, including low profitability from selling carbon credits.

However,

financial rewards for farmers are more common,

Geijer notes, adding that in order to meet their targets, dairy companies would have ‘a lot of missionary work’ to do, and that involves getting ‘large and diverse’ groups of farmers to rally behind these goals. Providing ‘proper tools and incentives will have a key role here, which in turn should hand more bargaining power to farmers.

But crucially, passing the extra costs of sustainability measures would be crucial to remain competitive. Strengthening partnerships with corporate customers – including FMCGs, retailers and foodservice firms – would be key, as those are the parties in the supply chain who would be looking for low-footprint products and require long-term commitments from suppliers. Another way is to seek a shift in product portfolios, e.g. through increasing the volumes of low-emissions products.

But passing down these increased costs to consumers is a less viable option, according to the research. “By itself, carbon reduction is not a key driver in purchasing behaviour of consumers,” Geijer says. “Aspects such as price, taste and health are far more important.”

Nevertheless, consumer price increase are likely, though ING doesn’t expect these to be steep. Geijer: “Will efforts from the dairy industry have an impact on consumer prices? We believe so, as they requires investment and efforts at both farms and at production facilities. (…) However, since dairy processors have a hard time in getting sustainability premiums from the market, we don’t expect any steep increases in consumer prices due to sustainability efforts in the near term.”

The report is available in full via ING’s website.